08:08

Most of us have many communication channels available to us today, including phone calls, emails, texts, instant messaging, and social media – not to mention our face-to-face conversations on video chats or in person. For all of this, we rely on our senses of sight and hearing.

But for a deafblind person, who has little or no useful sight and little or no useful hearing, they cannot rely on these two senses. Instead, they communicate through touch using tactile sign language – physically tracing some of the same symbols from American Sign Language (ASL), as well as some different ones. For these conversations, a communication partner will sit with a deafblind person, touch their hand and “fingerspell” what they are saying.

According to the National Center on Deaf-Blindness, there are 2.4 million people in the United States with combined vision and hearing loss.

It is estimated that only 10 percent of deafblind people are able to rely on traditional braille, which first requires learning the English language. Some people acquired deafblindness later in life or there were no resources available to them to learn. As such, the vast majority of the deafblind population can now only access communication if a person is sitting directly next to them.

While technology advancements have dramatically enhanced communication channels for other members of society, the deafblind community has remained vastly overlooked.

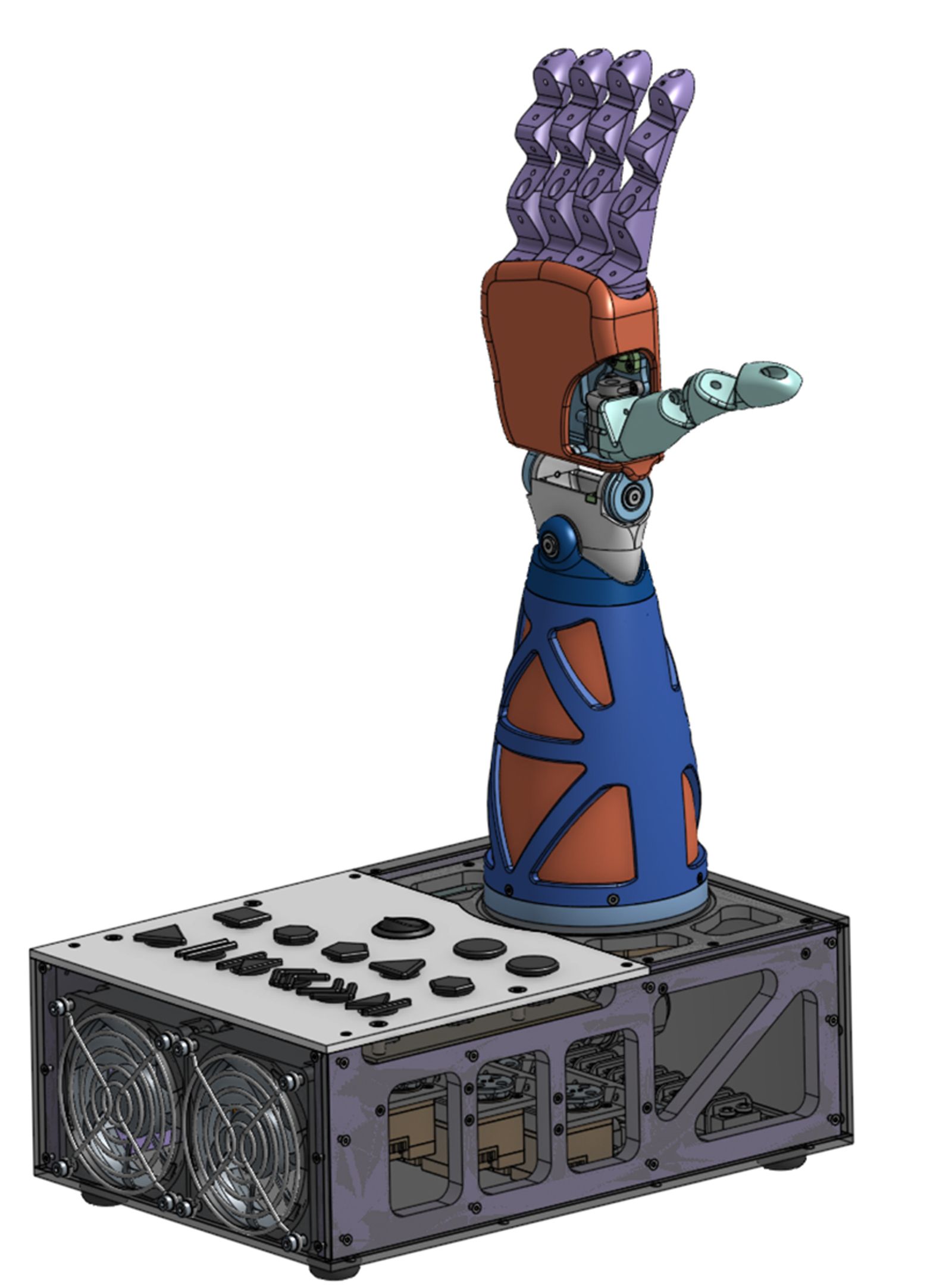

But now, Tatum Robotics, a Boston-based robotics startup, is changing that. The company is developing the first communication tools specifically designed for deafblind people. Their tabletop Tatum T1 robot, now in beta testing, can translate any speech or text into tactile sign language.

Samantha Johnson, founder and CEO of Tatum Robotics, recently joined PTC Chief Evangelist (and Onshape co-founder) Jon Hirschtick’s “Masters of Engineering” podcast to share her product development journey.

Samantha Johnson

“The T1 is a highly anthropomorphic collaborative robotic arm that deafblind people hold on to and touch like they would an interpreter to receive any form of communication, whether that be an email, a book, news source or website,” Johnson explained on the podcast. “And they can all access it via the cloud on their own time and customize their experience.”

The Tatum Robotics Origin Story

Samantha Johnson demonstrates how to use the T1 Fingerspelling robot. (Courtesy of Tatum Robotics)

Johnson’s path to developing this first-of-its-kind product started during her undergraduate days at Northeastern University in Boston. She was studying bioengineering with the goal of embarking on a career in assistive technology. As part of her courses, she took an American Sign Language (ASL) class as she thought it may be beneficial later in her career. During her studies, she attended a number of events, including one organized by the Deafblind Contact Center in Boston.

“I was chatting with a deafblind lady through an interpreter and was amazed at the amount of information she could receive directly into her hands,” Johnson recalled. “I asked her how she would communicate at home if the interpreter wasn't there. She said at home she is alone with no means of accessing communication.”

“I was immediately inspired to create a solution for this clear problem of isolation and loneliness. But being an undergrad, I didn't have the time or the skills to do anything at the time,” she added.

Johnson kept in touch with her contacts in the deafblind community. A few years later, when the Covid pandemic hit, she realized how much this community disproportionately suffers from isolation. They now had no communication with the outside world at all due to interpreters not being able to interact with them – an unintentionally cruel byproduct of social distancing.

After conversations with the Deafblind Contact Center, she decided to focus her master's thesis at Northeastern University on exploring solutions to this communication puzzle. Upon graduation, the Canadian National Institute for the Blind voiced their support of her thesis project and offered a grant to help fund continued R&D.

The grant money helped launch Tatum Robotics in September 2021, but Johnson had little experience in product development, especially in the robotic space. So she decided to move into the collaborative innovation workspace at MassRobotics, a Boston nonprofit devoted to robotics startups.

To help her build a tactile sign language robot from scratch, Johnson recruited a small team around her. This team of six, which consisted of full-time members as well as co-op graduate students from Northeastern, possessed a range of varied specialties, including: hardware design, mechanical engineering, software engineering, electrical engineering, robotics – and most importantly, linguistics. Creating software to translate English to tactile sign language was crucial to the success of the product.

Creating an Accessible Robotic Tactile Sign Language Translator

Volunteers using Tatum’s robotic tactile sign language translator. (Courtesy of Tatum Robotics)

From the earliest days of her startup, Johnson realized that making an accessible robotic sign language interpreter meant designing an affordable one. The technology wouldn’t achieve much good if it was out of reach of the people who needed it the most.

“To keep costs down, we decided to design as small as possible to start with, figuring out what works and then adding in additional functionalities as we saw fit,” Johnson recalled. “For instance, our first system only had three degrees of freedom in the index and middle finger. We then realized we needed that in all of the fingers, but didn’t need it in all four joints, we could just do three. So we started adding in those features as we went along.”

While some of the robot components will eventually be manufactured using machining or molding, the Tatum team made significant use of 3D printing for early prototypes. The T1 hand went through numerous iterations because the team was designing a product for a user group who had never been served before in the robotics space. Partnering with a number of organizations, including the Deafblind Contact Center and Perkins School for the Blind in Boston, the Tatum Robotics team used those prototypes to conduct user testing with deafblind people as well as those working with the deafblind community.

“We learned that we had to manipulate the haptics in a variety of ways to make it customizable for a wide variance of people's skill levels, from a really experienced tactile user to someone who is just learning tactile sign language. So there's been a lot of challenges trying to make our design as holistic as possible,” Johnson said.

Onshape: The CAD for Startup Tatum Robotics

The Tatum T1 in Onshape.

Designing a complex robotic arm from the ground up is a huge challenge, especially for a team of just six people. Rather than getting buried under the enormity of the full company mission, Tatum Robotics follows an Agile Product Development approach that includes weekly sprints – short timeframes for completing a design task.

“These mini sprints keep both the hardware and software teams focused on what needs to get done,” noted Johnson. “As we’ve discovered, if you are working towards a specific goal, you can get a lot done in a week.”

In an effort to be more agile, Tatum Robotics is a participant in the Onshape Startup Program. The company’s hardware development team switched from their old file-based CAD system to Onshape, a cloud-native platform with built-in PDM (product data management) and real-time collaboration tools. Cloud-native PDM requires no check-in/check-out protocols that lock files. Multiple people can simultaneously work on a design without fear of overwriting each other’s work. Whenever one engineer makes a design change, everyone else on the team can instantly see it.

“For our hardware team, having that automatic version control is pretty huge. As we’re iterating, we can easily see what changes have been made from earlier versions and what has stayed the same,” Johnson said.

“One of my main concerns is security,” she added. “As we work with many partners serving the deafblind community, we often share our designs to get feedback. With our previous CAD tool, we would send a file and it would be gone and out of our reach. But a benefit of Onshape is that you can easily share a design with someone and then withdraw access just as quickly. That is a huge advantage for us.”

Johnson said the Tatum team also values the always-on simulation tools built into Onshape, giving designers finite element analysis (FEA) early in the process – ultimately leading to stronger and safer products.

“Being able to do FEA directly in Onshape is very exciting. For example, we can find out early on why a finger bracket is warping and use the analysis to improve the design,” she says.

Getting Paid in Hugs

As Tatum Robotics enters its beta release phase for the Tatum T1 – giving the robot interpreters to a wide range of people to test in their homes for eight to 12 weeks – Johnson feels grateful for the reception she’s received from the deafblind community.

She revealed to “Masters of Engineering” podcast host Jon Hirschtick that she’s been “getting more hugs than she’s ever received” in her life.

“There are some deafblind folks who have been on this product development journey with us helping test prototypes as it has progressed from making very simple shapes to becoming very realistic,” said Johnson. “My favorite part of the job is the excitement from deafblind people when they realize this is something they could be using everyday soon.”

(To listen to Samantha Johnson’s full “Masters of Engineering” conversation with Jon Hirschtick, click here.)

The Onshape Startup Program

Equip your team with full-featured CAD, built-in PDM, and real-time collaboration in one system.

Latest Content

- Case Study

- Aviation, Aerospace & Defense

Dufour Aerospace Accelerates Critical Cargo Drone Delivery with PTC’s Onshape and Arena

02.11.2026 learn more

- Blog

- Evaluating Onshape

- Collaboration

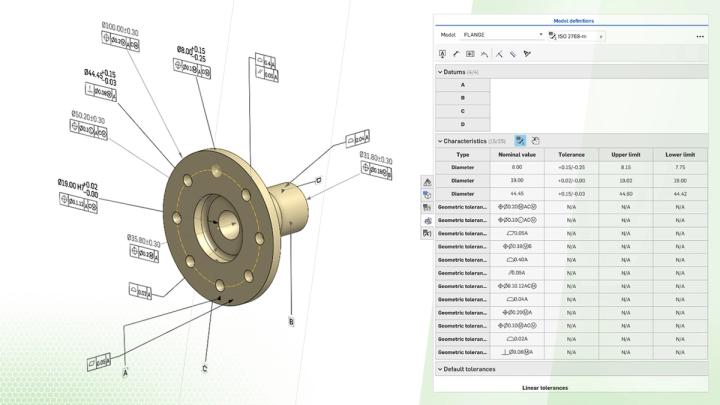

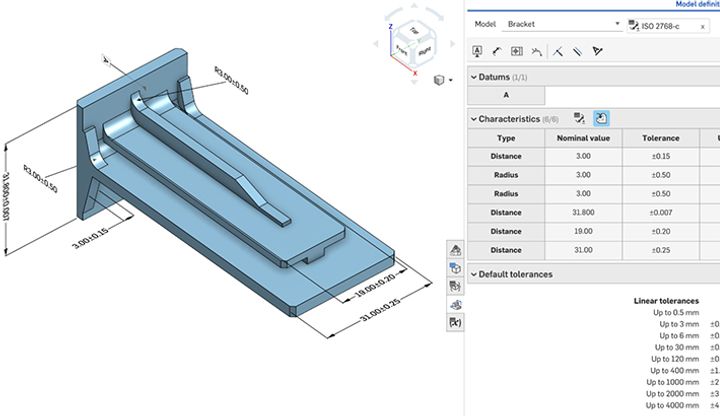

How Onshape Fixes the Broken Promise of Model-Based Definition

02.26.2026 learn more

- Blog

- Customers & Case Studies

- Automotive & Transportation

Powering Heavy-Duty Innovation: How Edison Motors Builds Next-Gen Hybrid Trucks with Onshape

02.26.2026 learn more

- Blog

- Evaluating Onshape

- Education

- Education & Universities

Future-Proof Engineering Education with Model-Based Definition in Onshape

02.24.2026 learn more